This is not the only one. Many people ask for proof of Rajputs prior to even 1300-1500 AD.

So let’s use this opportunity to enhance our understanding. What is the story of this term Rajput or Rājaputra?

The evidence

Literal meaning of Rājaputra is – son of a King or royal child. Earliest recorded reference to this term are in Aitareya, Taittiriya and Sathapatha Brahamanas of the Rigveda. People who have been called rAjaputra in these scriptures include Vishwamitra.

To pick one instance – Aitreya Brahmana 7.17 has Sunahsepa’s father calling Vishwamitra as a Rājaputra. Vishwamitra was no prince. That he owned land is clear from the fact that he declared Sunahsepa’s father as rightful owner of his primogeniture (jyaisthya).

Ramayana’s Balakanda has the same Vishvamitra calling King Trishanku a Rājaputra. And barely two verses before that address, Trishanku is called a Rajana.

Later the term Rājaputra appears in Kathaka Samhita and other vedic literature compilations.

Then in Mahabharata 3.266.61 (Ramopakhyana), lord Rama and Lakshmana are called Rājaputras when they bid farewell to vānara rāja Sugreeva:

राजपुत्रौ कुशलिनौ भरातरौ रामलक्ष्मणौ

सर्वशाखा मृगेन्द्रेण सुग्रीवेणाभिपालितौ

Shanti parva of the Mahabharata, chapter 62/63/64 (depending on which recension you pick) verses 9 and 14 use the term Rājaputra to simply mean Kshatriya on multiple occasions. For example when it is speaking of three Varna’s legitimacy to take to asking alms for food. It says as follows:

Another instance from Mahabharata Adi parva is of when King Dushyanta refers to Shakuntala the daughter of Rishi Vishwamitra as Rajaputri. One has to keep in mind that at the time of this conversation Vishwamitra had long been a sage and no longer a kshatriya.

सुव्यक्तं राजपुत्री तवं यथा कल्याणि भाषसे

भार्या मे भव सुश्रॊणि बरूहि किं करवाणि ते (1.67.1)

Yet the word used is Rajaputri which clearly establishes the significance of bloodlines that seem to override the identity based on what one might be doing over the past few years or decades.

Adi parva again. King Yayati speaks thus about himself:

ब्रह्मचर्येण वेदो मे कृत्स्नः श्रुतिपथं गतः। राजाहं राजपुत्रश्च ययातिरिति विश्रुतः ॥(7.81.24)

Translation : I have studied all the Vedas from Shruti tradition with Brahmacarya. I am a Rajputra and the king. I am called Yayati.

He introduced himself as a King (title/position) and a Rājaputra (ancestry) at the same time. It wouldn’t be the case if Rājaputra only meant prince or a position based title.

Many of the itihasa texts discussed above, like the Mahabharata have their oldest surviving manuscript dated to late ancient era. Why we reminded our readers about this will be clearer with the Pali literature examples given below.

Similarly, Shrimad Bhagvatam 1.12.311 calls Abhimanyu’s son Parikshit a Rājaputra.

As is well known, various buddhist texts call Budhha a Rājaputra.

Next, Kautilya’s arthashAstra 3rd-4th century BCE and Kalidasa’s mAlavikAgnimitram 1st century BCE refer to Rājaputras on multiple occasions.

In broadly the time frame of 3rd to 1st centuries BCE the Pali Canon literature is seen using Rājaputra interchangeably for Kshatriyas.

Like the SobhitaBuddhavamso (14th book within Khuddaka Nikaya) in its verse no. 6 equates Rājaputra (Rajaputto) with Kshatriya (Khattiyo). It speaks of a kshatriya named Jayasena Rajaputra[1].

Punaparam rajaputto, jayaseno nama khattiyo;

Aramam ropayitvana, buddhe niyyaday! tada.

Again from the same centuries, we have the Sundarika Bharadvaja Sutta under Sutta Nipata (section 3.4) of Khuddaka Nikaya. It narrates that when a brahmin named Sundarika Bharadwaj notices Buddha, and out of curiosity desires to inquire his ancestry. His words are – jātim puccheyanti i.e. I shall ask for his caste/ancestry.

To this query the Buddha himself responds thus: [2]:

न ब्राह्मणो नोम्हि न राजपुत्तो, न वेस्सायनो उद कोचि नोम्हि।

गोत्तं परिञ्ञाय पुथुज्जनानं, अकिञ्चनो मन्त चरामि लोके॥

“I’m not a brahmin, a rajput, a vaishya or anybody else. I don’t identify myself with the typical gotras. I just dwell in this world only by my wisdom.”

It can’t get easier than the verse above to establish Rājaputra and kshatriya as synonyms in usage. We know that kshatriya was a word reserved for not only the princes, rather for members of the society that looked after the administration & defence. It isn’t hard to deduce that ‘Rājaputra’ which is used interchangeably with ‘Kshatriya’ carries the same connotation.

A silver coin of Amoghabhuti (2nd-1st century BCE) the ruler from Kuninda kshatriya clan contains – “Rajnah Kunindasya Amoghabhutisya Maharajasya“.

Notice that despite taking up a boastful title of Maharaja, the King is still sticking to the traditional clan head title i.e. rAjnah. Because his was a kshatriya clan-based Kingdom held together by his clansmen. This was the norm and not an exception. It continued even in medieval times as we shall see.

The Prashnopanishad (dated 1st century BCE or earlier) has the following words for Rājaputra of Kosala country.

भगवन्हिरण्यनाभः कौसल्यो राजपुत्रो मामुपेत्यैतं प्रश्नमपृच्छत

Shankaracharya in his commentary of this Upanishad has explained it as ‘a Kshatriya born in Kosala’, probably because it doesn’t read as ‘Kosala Rājaputrah’ for it to be called ‘Prince of Kosala’. The phrase used by Shankaracharya is:

कौसल्यो राजपुत्रो जातितः क्षत्रियो i.e. a Rājaputra of Kosala who was kshatriya by birth.

Asvaghosha’s (80-150 A.D.) Saundarananda refers to Rājaputras at its Sarga 1 shloka 18. Context is that some rAjaputras of Iksvaku vansha have come to the ashrama of sage Kapila Gautama to live there:

“अथ तेजस्विसदनं तपाक्षेत्रं तमाश्रमम् । केचिदिक्ष्वाकवो जग्मू राजपुत्राः विवत्सवः।”

[3].

Numerous Gupta and Lichhavi inscriptions use the term Rājaputra for men who were not even close to being princes i.e. small chieftains regardless of age, governors of various localities, middle rank officers, etc.

In the 569-70 A.D. Sumandala copper plate of Dharmaraja, an almost independent feudatory of Prithvi Vigraha is referred to as a Rājaputra.

Lichhavi king Gangadev’s Shankhamula inscription (567-73 A.D.) refers to Rājaputras Vajraratha, Babharuvarma, and Deshavarma.

The Five Damodarpur copper-plate inscriptions of the Gupta rulers have Rājaputra epithet, such as those of Kumaragupta III 533 A.D.

One of them reads thus – ‘Rajaputra Deva-Bhattaraka uparika Maharaja‘.

In the Sanga (Nepal) inscription of late 5th century A.D. its dutaka the Chief Minister under Amsuvarman is called Rājaputra Vikramsena. His relative in another inscription is called Rājaputra Shurasena. [4]

Many more Nepalese (Lichhavi) inscriptions in Gupta characters found by Italian scholar Raniero Gnoli refer to Rājaputra Jayadeva, Rājaputra Shurasena, Rājaputras Nandavarma, Jishnuvarma and Bhimavarma.

Emperor Harshavardhan gets crowned in 606 A.D. at Kannauj and despite being a King, he continues for many years with the epithet Rājaputra shilAditya.

In the mid 7th century AD we see small chieftains like Janardana Varma in Batuka Bhairava temple inscription at Lagankhel, Nepal referred with the prefix of Rājaputra. He is also seen donating money for water channels [5].

Outside the official inscriptions, the 7th century public literature of Banabhatta like the Harshacharita and Kadambari begin to use the word ‘Rajaputra’ in terms of macro lineal descent. Another example from Kadambari (Poorvabhag, Pg 13, Credit: https://twitter.com/Dudore_0309/status/1307271094991167489) also talks of a Malava Rājaputra named Madhavgupt.

“( पुष्पभूतिस्तु ) अपरेयुः उत्थाय कतिपयैरेव राजपुत्रैः परिश्तो भैरवाचार्य द्रष्टुं प्रतस्थे । “

” केसरिकिशोरकैरिव विक्रमैकरसैरपि विनयव्यवहारिभिरात्मनः प्रति विम्वैरिव राजपुत्रैः सह रममाणः प्रथमे वयसि सुखमतिचिरमुवास ।”

This is also corroborated from his mention later in Apshad inscription of the 8th century [6].

We saw many crystal clear examples indicating Rajaputra being used interchangeably with Kshatriya. But from this transitive phase, when did the Rajaputra term get popular usage almost exclusively within a specific, easily distinguishable community connotation?

When does the term Rajaputra begin to indicate a separate and clearly identifiable Jati?

The answer ties to wider social moorings of North India.

It is basic etymology that Rajaputra depicts the notion of lineal ancestry better than the word Kshatriya.

The post Gupta age was characterized by the twin aftermath of Arab invasions and further consolidation of Jatis. Son does what father does. Son holds what the father holds. It shows up also in the late Gupta era and early medieval inscriptions where the son or relative of a Rajaputra is found addressed again as a Rajaputra.

These catalysts brought accelerated politico-military and administrative changes in the 6th to 8th centuries A.D. north India. Examples of it would be feudal armies and land ownership transfers from one lineal generation to another. Earlier these used to be centralized State prerogatives only.

The changes toward feydalism picked pace toward the end of Gupta era. In contrast to ancient Republics, the State began de-centralizing and outsourcing the administration via privatization of land ownership. Thus, the ancient kshatriya clans wherever they were, evolved into small to mid-sized feudalistic Kingdoms. With feudalism came the fixation of bloodline-based kinship in administration and the State’s institutional apparatus.

Over the next centuries the clans continued to fall and rise around the revolving door of time, but the political and administrative pattern persisted. These were later known as the various Rajput Kingdoms.

Observing this transformation helps us understand why witnesses like Hiuen Tsang mention at the start of 7th century A.D. that the King of Ku-Che-Lo country sitting in his capital Bhinmal, was a young lad who was “Kshatriya by birth”.

After Arab invasions, in north India Rajaputra gradually began to replace the word Kshatriya as the prominent term of usage.

It is in this twin aftermath backdrop that the term Rajaputra, which is found plenty in literature since Rigveda, gained macro prominence. Because now lineal descent was an important and urgent need for the twin reasons mentioned above.

Arab travellers of 9th century A.D. acknowledge rAshtrakutas aka Vallabh-Raj or Ballah-Raya or Al-Ballahara as the greatest King in India and one of the 4 most prominent Kings in the world. It is an established and well known fact based on epigraphic evidence that the medieval centuries’ Rathore Rajputs are descendants of these Rashtrakutas.

9th century copper plate grants of Bhanja dynasty rulers from Orissa, such as the Dasapalla plate, ones of Ranabhanja Deva, Shatrubhanja I, etc have the term ‘rAnaka’ used for many princes and small chieftains. It is a distortion of rAjanka / rAjanaka and got further shortened to rAnA over time [7].

The Basahi/Bisahi grant of prince GovindaChandra of Rashtrakuta branch named Gadhavala/Gahadvala, dated 1104 A.D. calls him mahArAjaputra [9].

1143 AD inscription of his son shows the same title and is in the name of mahArAjaputra rAjyapAladeva.

1134 AD Inscription of Singar/Sengar family who were feudatory of Gadhavalas, is in the name of mahArAjaputra vastarAjadeva [10].

10th century text from rAshtrakuta rule called Yasastilaka Champu describes rAjput military camps as follows: –

Camp Name – skandhavara

Arsenal in charge – mahAyudhapati

Cavalry in charge – asavapati

Infantry in charge – paikkadhipati

Elephant in charge – pilupati

Soldier description – Dhoti coming up to knees. Loins girt with daggers mounted on handles of buffalo horns. Hair on body. Quivers on either sides of head. Experts in shooting arrows.

Military titles – senani, thakkura, kottapAla

Feudal titles – rAjA, rAjakula, mahAsAmanta, mahAmandalika

Most of these titles are common with Pratiharas as well.

Most important evidence: –

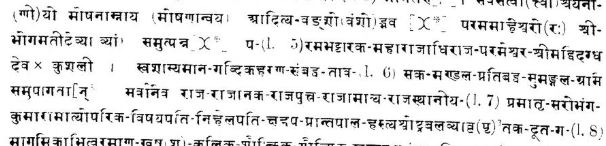

Given below is part of the Chamba copper plate inscription of Vidagdha Verman of 960 AD regarding a land grant in village Sumangala [11]. Inscription names all concerned functionaries and state officials etc of the village Sumangala in a huge list. Notice the terms in line 6 – rAja-rAjAnaka-rAjaputra-rAjAmAtya-rAjasthAneeya. Clear indication of these being land owning gentries with administrative or military skills. Vidagdha Verman was a Suryavanshi rAjaputra of Mushana dynasty (moshuna gotra).

Similar list with terms like rajanyaka-rajani-ranaka-rajaputra are found in many other inscriptions from east like those of Sena rulers such as VallalaSena and LakshamanSena [12]. Each of these copper plates – from Naihati , Anulia, Govindapur, TarpanaDighi & MadhaiNagar – consistently portrays a whole hierarchy of landed gentries from Rajana to Rajaputra.

It isn’t that only the word kshatriya has been used to mean kshatriyas throughout the literature. Even in the Rigveda’s famous purusha sookta verses, the term Rajanya is used as connotative of kshatriyas.

The effects of feudalism are abundantly clear by the time of 1077 AD Kahla grant of Kalachuri King Sodhadeva. His genealogy mentioned in this grant begins with a “Shri Rajaputrah”, which is obviously a filler for lack of information. But the choice of word for a filler is quite telling, given that the grant is speaking of the family’s progenitor. Not some upstart princely youth amidst them.

At the same time the kathAsaritasAgara of Somadeva around 1070 AD, writes of two crooks named Shiva and mAdhava. Of them mAdhava takes the getup of a Rājaputra. This was done to avoid capture as he would be seen as an elite i.e. officer/land-holder/soldier etc. So that nobody would trouble/suspect him.

राजपुत्रस्य वेषेण तस्यौ ग्रामे कचिद्वहि:[13].

Throughout the story this mAdhava has no connection with being a prince. Even the King in the story receives him in grace and employs him on a salary. If we were to assume that Rājaputra meant a prince then, obviously no crook out to execute his trickery will be foolish to take the getup of the prince of a Kingdom and then step out to have all attention under the Sun to fall on himself.

The text has many other examples like:

– A story of a Pataliputra king named Vikramaditya going on covert mission in enemy territory with 500 Rajaputras. Our skeptics should wonder how there can be 500 princes or even highest officials under a King. By the way, the story names the ministers separately, so Rajaputras is clearly meant as a militarized-administrative land holding gentry. [14]

– Later Vikramaditya asks his minister to take away with him to Pataliputra the disguised Rajput retinue (of those 500 men) in following words.[15]

वेषच्छन्न समादाय राजपुत्रपरिच्छदम्

Please amuse me if anybody thinks that this means 500 princes!

– One story depicts how the King Ugrabhata of city Radha got angry at his elder son Bhimabhata for beating the younger step-brother named Samarabhata. As a punishment King took away 100 rAjaputras from Bhimabhata’s allowance and posted them to guard Samarabhata instead.

ह्यतवृत्तिं च कृत्वैनं राजपुत्रशतं व्यधात्। रक्षार्थ तस्य समरभटस्य सपरिच्छदम्।।

It becomes imperative to ask in which world are 100 princes found employed for guarding (as salaried staff) one prince of another King? [16]

– Next, another story in the text introduces a Rajaputra named Shurasena who was the ‘sevaka’ of a King and had a village’s revenue allotted to him for sustenance.

Since when, one might ask, have princes started serving other Kings, living off a village’s proceeds? That is same as the vastly prevalent signature of a typical land owning Rajput official employed with the State. [17]

A known and basic fact of linguistics is that the written literature of any age & languages typically applies the terminology that has been in currency in the society for sometime. Hence (considering the time kathAsaritasAgara was written i.e. 1070 AD) we can easily and confidently state that even before the start of 11th century AD, ‘Rajaputra’ meant a community, a landed gentry and not just a prince or few topmost officers anymore.

Let us return to some epigraphy but 11th century onwards now. The Kadmal plates of Vijayasimha Guhilot 1083 AD mention that a messenger named ranadhavala, son of sagamdA was a Chauhan rAjaputra [18].

Udayagiri cave inscriptions near Bhopal dated end of 11th century AD mention land grants by many minor paramAra chieftains named- rAjaputra dAmodara jayadeva, rAjaputra Sodha, rAjaputra vAhilavAhada [19]

Paldi inscription of 1116 AD says that Saulanki rAjaputra Sri salakhana was the son of rAjaputra Sri Upala. Former was just an officer tasked with the arrangements for the cermeonies around installation and sanctifying of the inscription.[20].

The reign of Jaichand’s predecessor in 12th century AD. A vassal dynasty of Gahadavalas, known as Dhavalas records themselves in Taracandi rock inscription at modern Shahabad, UP. The inscription calls the overlord Gahadavals King’s son (Jaichand) as mahArAjaputra as well as the Dhavala prince srI satrughnasya as mahArAjaputra.

The infusion of royal blood and administrative fiefs in the term Rajaputra is indicated in the 12th century as well. Rajaputra had now long been frequently applied outside of the young princes sprinting in palaces.

Few more examples:

a) Sallaksanapal though a minister of Vigraharaj Chauhan IV, is called a Rajaputra in the Delhi Shiwalik inscription of 1163-4 A.D. [21]

b) Two inscriptions of 1176 AD at Lalrai (near Nadol) call Lakhanapala and Abhayapala Chauhan the relatives of Nadol King Kelhana as Rajaputras. Points to note are:

- they were not in-line for any throne

- they were just given administrative posts to govern some villages and yet called Rajaputras.

This is supported by KharataraGachchaPattavali [22] and PrabandhaChintamani [23] which show various ‘Rajaputras’ appointed as governors/administrators of mandalas, towns and villages.

c) Nadol copper plates of 1161 A.D from South Rajasthan proclaim the local Chauhan lineage’s progenitor and King Kirtipal Chauhan as rAjaputra.

d) Jaypura (Bihar) inscription of 12th century AD calls a Gupta dynasty’s Krishnagupta as rAjaputra.

e) Hemachandra’s Trishashti ShalAkA Purusha Charita of 12th century AD refers to numerous personalities of rAjaputra descent.

f) Jalor Stone Inscription of Kirtipala’s son SamaraSimhaDeva from 1182 AD refers to a Rajaputra Jojila Chauhan. He was no teenaged in-line-for-throne royal, but the maternal uncle of SamaraSimha. Thus he was aptly also called Rajyachintaka in the same verse.[24]

All of the data above establishes even if we remain apprehensive of rAjaputra being a macro synonym of kshatriya from the beginning (rigveda). We have to concede considering the evidence unloaded above that it happened long before the purported 650 or 1300 AD. Rajaputra is used not only for princes, but frequently and abundantly for a specific, distinguishable community;in transiting through a time when it is used for the chieftains and then officers, land holders, governors, elite soldiers etc. Even the messengers, soldiers and administrators of ceremonies are rAjaputras. By the start of medieval age the state of usage of the term rAjaputra is that application is regardless of whether one was currently a prince, chieftain, son of chieftain or neither – even if just an official, salaried soldier or functionary. This is obvious if Rajaputra is indicative of a whole jati/varna containing rulers, officers of a hierarchy and others who were close-by in their clannish brotherhood. The variety in application demonstrated above is impossible even if the term meant only a title. Why this change could not have been exposed to non-kshatriya social groups; as in anybody could use the title and voila they’re a rAjaputra, is easy to see by surveying the social setup of late ancient and early medieval India.

Another strong case of group connotation for Rajaputra is Kalhana’s (12th century A.D.) Rajatarangini. It uses the term rAjaputra a lot of times in numerous contexts including – for the gentry of general land holders who contributed militarily. For example, one verse describes the 11th century King Anantadeva being followed by a host caravan of ‘bands of rAjaputra horsemen, soldiers and damaras’. [25]

Even by stretch of imagination these bands of rAjaputra horsemen can’t be all princes (how many could be there anyway). Also the previous verse uses the term Nrapatmajah for princes.

Thus whenever princes and Rajputs were spoken about in vicinity in the text, the author of Rajatarangini has been careful to strike clear distinction between princes (called Nrapatmajah) and the noblemen (called Rajaputras).

Similar instances from the Rajataramgini are of:

- Tungga going to Shahi lands of Trilochanpala with a powerful army having – many feudatory chiefs, ministers and Rajpautras. [26] Certainly, the Rajaputras were not “just another soldier” at the time of Rajatarangini (12th century).

- Wife of the King Anatadeva was, after his death, giving due salaries to – “all gentries employed with the State right from the Rajaputras to the Chandalas”. What clearer example can there be of Rajaputras becoming a recognized, full fledged and elite section of the society, no longer just some individuals like a prince or chieftain,governor, etc [27].

Finally, the evidence of Thakkur Pheru’s DravyaPariksha. This early 14th century text speaks of various coins and identifies many of the Delhi based coins as those of the Tomara Rajaputras. It is not tough to understand that neither princes nor a random official with ‘Rajaputra’ title can mint coins in their name. This prerogative was held by Kings only. Which leaves us with only one valid interpretation of Rajaputra here.

Since the Tomara Kings belonged to a particular section of the society (Rajaputra). The same identification persists in the text. The fact that this notion has reflected in an early 14th century text, denotes that the Rajaputra identity continued to be a well-formed social currency even in the 13th century.

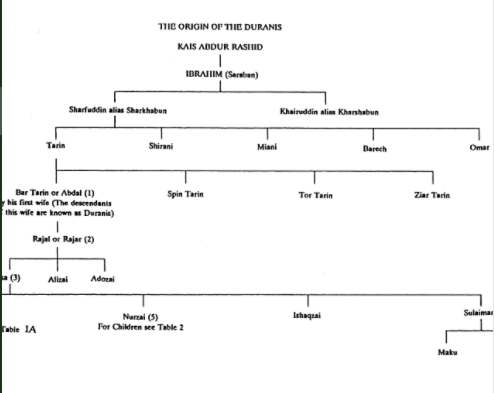

Afghan genealogies also provide interesting insights on this journey from a unique angle. Henry Walter Bellew, an authority on Pashtun history concludes that Saraban/Sarabani one of the earliest afghan ancestors is actually a corruption of Suryavansha/Suryavanshi. It can’t be discarded as an isolated anomaly because the sons and grandsons of this Saraban are named in the genalogies as Krishyun, Sharjyun and Sheorani which are easily discernible as variations of Krishna, Surjan, etc. [Credit: twitter handle @HinduAfghan]

The data that Bellew collected from Afghan genealogies gets first hand corroboration when Sir A. H. MacMahon conducts another study. Following is the diagram based on what the Durrani leaders told him about their ancestors.

When Bellew later expanded his scope to a proper ethnological study. He also found sections in the same afghan genealogies bearing striking similarities with names that are of well known Rajput clans that have lived in medieval northwest India. Few of them are :

Baddo under Utmanzais – Yadu Kshatriya/Rajput

Gadun of Hazara – Jadaun Rajputs

Yaduvanshi migration toward northwest is a recurring literary theme since the immediate aftermath of Mahabharata to the early hisotry of the medieval yaduvanshi Bhati Rajputs.

The memory of this less known overlap persists as Ferishta notes that the iconic Ghori-Prithviraj clash of Tarain involved Hindu afghans of the same Sulaiman mountain range fighting on Prithviraj’s side [The North-west Frontier of Pakistan, Syes Abdul Quddus, Pg 79]

Some allegations

Let us take a detour to address some charges. It is often alluded rather ludicrously that Rajaputras are a mixed caste i.e. born of an illegitimate union of caste x and caste y.

To support, a verse from Brahmavaivarta Purana is quoted.

क्षत्रात्करणकन्यायां राजपुत्रो बभूव ह ।।

राजपुत्र्यां तु करणादागरीति प्रकीर्तितः ।।

~ब्रह्मवैवर्तपुराणम् [28]

Translation : With the union of a Kshatriya and a Karana kanya, Rajaputra was born….

Based on the textual analysis and observing the details of perusal or not of this Purana in contemporary medieval literature. Many scholars such as J. C Roy and R. C. Hazra etc have concluded that all the currently available copies of Brahmavaivarta Purana were composed starting 15th-16th centuries AD onwards in the Orissa-Bengal region.

Among others, the interpolation of chapter 10 from Brahma khanda has been placed after the 16th century AD. This is the chapter on mixed castes and is the one in which the said verse is found.

So far as the Karana kanya mentioned in the verse is concerned. The Karana caste has historically existed only in the Orissa-Bengal region.

Conclusion – whoever interpolated this chapter in the Purana after the 16th century, they wrote with their limited social context of Bengal-Orissa only. Whatever they saw or wrote i.e. Karanas doesn’t apply on the kshatriyas/rajaputras of the rest of India.

Another mischief is to quote a verse from the Sahyadri Khanda that claims to be part of Skanda Purana. And then assert that the Rajputs are mixed progeny of Brahmins and Shudras.

This fallacy is perpetuated by hiding the fact well known in academic circles, that the Sahyadri Khanda has had some interpolations dated after 15th century AD. This verse being an example of the same gets clear the moment you look at:

a) Composition. Observe the chapter it is from. That whole chapter has been highlighted by scholars as a post-15th century interpolation.

b) Linguistics. Particularly the word ‘रजपूत’ in the verse. This word is a late medieval feature that appears even after the apabhramsha based राजपूत. The author who quotes the verse himself confesses that this verse is explaining an apabhramsha word. This word is not seen in literature before the 16th century AD.

Also note that both BrahmaVaivarta Purana and the Sahyadri Khanda have a limited geographical context of Bengal-Orissa and the South. Whereas the change of using Rājaputra as the in-fashion word for Kshatriyas happens and stays for long in a concentrated zone of north, north-west and west India. Hardly any overlap and applicability whatsoever.

But why should that stop those who’re hell bent on distorting history.

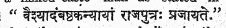

The same results come out when you look under the hood of another claim that Parashara Smriti calls Rajputs a mixed caste via:

It has already been refuted by scholars like Chintamani Vinayak Vaidya as plain-in-sight and late interpolation. This because none of the earlier and well-known recensions of the Smriti have this line.

One can only pity the social media trolls who flutter these citations like robots, without even understanding them or their veracity/controvertiality.

Sociologistic trash at Wikipedia

There’s also a new disease spreading on the Wikipedia these days. Where the ill-informed words of some sociologists shallow citing other western scholars, has been used to claim that Rajputs as a community didn’t exist before the 16th century AD.

One such case is of Cynthia Talbot. Her assertion of change in nomenclature for social groups such as Kshatriya to Rajput has been abused to imagine and claim that ancient Kshatriyas and medieval Rajputs are two disjoint genealogical sets.

These hollow claims would have us believe that when Bhārata became known as India it must have been emptied and populated by different people, because, well the geography is same but the name changed right? And again when it became Hindustāna it would have re-peopled with new stock. Such are the arguments we’re supposed to buy.

It must be stressed that neither Talbot has said that Kshatriyas and Rajputs were two different and disjoint people. Nor she was in a position to say so. When she by her own admission states that her work is not of researching history but that of tracing a memory in the history.

Moreover, there are no apocalyptic jolts recorded in the consistently well populated north India that could wipe out its Kshatriya stock (only the Kshatriya stock); then also pave the way for an imaginary introduction of Rajputs from non-kshatriya origins.

Yet, a nuance of shift in popular nomenclature has been exploited to imagine genealogical separations that don’t exist.

When propaganda is an objective, who cares for what the history truly tells us.

These are classic scenarios of lies standing tall on long and thin legs.

Notice that the vague, broad brushing assertions aren’t even backed up by citations or evidence.

The very word Rājaputra screams its etymology to clarify all doubts, provided the person hasn’t tied himself in knots.

Rāja is royalty, that is – Kings, royal family, nobles (second ring of elites). Putra is direct progeny as well as extended family by wider relations. The word’s meaning has lineal descent naturally embedded in it i. e. by design. This simple yet profound fact stands ante to whatever stunts anybody may want to pull, such as “it was an admin position”.

If we take Cynthia Talbot also at face value (since she too doesn’t mention her sources). It crashes us into her atrocious statements, like Raso mentioning that Jaichand calls Ghori to India for fighting against Prithviraj Chauhan.

1200–2000, Pg 111

Fact? There is absolutely no such mention in any copy of the Raso. It on the contrary praises Jaichand for putting Ghori into fear. See below:

So, the less said of Talbot the better.

Coming back to the topic, all the above mentioned evidence was not an exhaustive list, but only some examples. It becomes an even larger list if we were to include occurrences of other closely associated terms in vogue that came out similarly – Rawal from rAjakula, Rajanya, rAjini (women), mahArAjini, also rAjanaka, rAjanka ranaka, rAnA, Rao, Rawat (from rAjaputra) etc.

Crux of the tricks

We have already seen that use of the word “Rajaputra” for Kshatriyas/Rajputs as a social group became predominant fashion in society 10th century onwards.

The crux of distortions is in subtly twisting this simple fact and saying instead – that the Rajputs as a people themselves originated only in the 10th/13th/15th etc century of the AD.

Then there are some geniuses who like to suggest that most if not all of the Rajputs were originally Shudras. That’s funny! If present date Brahmins are descendants of Vasishtha, Bharadvaja, Mudgala, Kaushika. Then how come Rajputs are not descendants of Vedic Kshatriyas. Did the latter disappear in thin air? Or was there a selective pandemic that killed only the ancient Kshatriya lineages. Various Kshatriya clans rose and fell in northwest India from the vedic times and are recorded since Panini. The medieval Rajput clans are just a continuation where the dominant term used now is Rajaputra instead of Kshatriya.

Last words

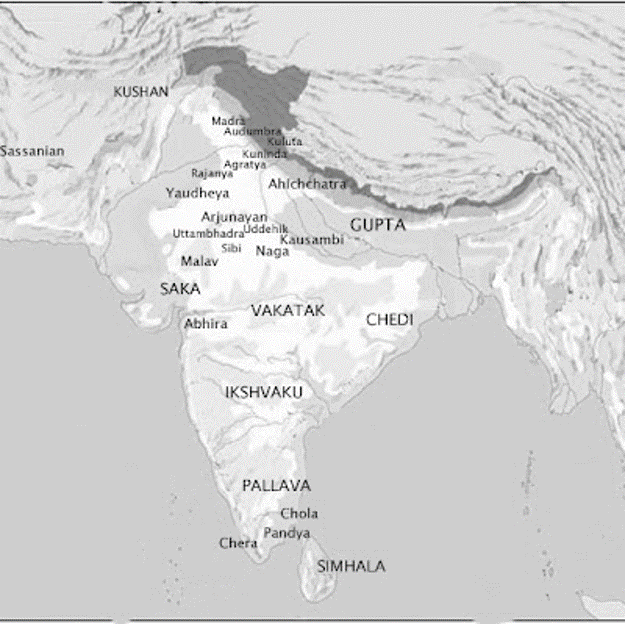

Following is just one point in time snapshot of ancient Kshatriya clans straddling the entire north and west of India. Notice that one is even named rAjanya, suggesting that the whole warrior clan was of kshatriya pedigree in the royal ambit.

From the highly centralized system of ruling with Mauryas to the decentralized Gupta empire. There came a huge change which became precursor to format of medieval Kingdoms. Imperial centre (native as well as foreign origin) would just exact tributes from smaller Kingdoms, require their armies in campaigns and leave them be with local sovereignty. Thus, an oscillation between – subdued local Kingdoms paying regular tributes when Imperial centre is strong. And revolting, tribute-withholding local Kingdoms when Imperial centre was weak. This formed the bedrock of upcoming feudalism or state level focus in a politically divided India, signs of which had shown up during Kushan rule itself. Thus, the clans who were prominent in each of these clan-based kingdoms would attach their loyalty and focus only to their own local Kingdom and its ruler; not the Imperial centre.

Guptas were perhaps the first native Empire to rule such an increasingly de-centralized setup lacking proper semblance of a united politico military nationality. With this, armies everywhere became more clan based, fragmented. Further, land grants and power delegation from Imperial centre thus started going by default to the clan based hereditary successors. A big change from the days of Mauryan Imperial centre when State wouldn’t deal in outsourcing administration on land basis. Parting from ancient republics the various kshatriya clans wherever they were, evolved into Kingdoms and the land ownership was private now. Of course new clans kept replacing old ones as usual. All these transformations continued throughout Gupta rule, Harshavardhan and show complete with the appearance of Imperial Pratihars in domination. By the time of Guptas already, the princes were regularly using hierarchical titles like mahArAjaputra DevabhAttarak.

Harshavardhan had driven out the last remnants of pre-Islamic foreign origin rulers, except the miniscule numbers who mostly adapted to get absorbed in the society without leaving distinct traits. Thus before the dawn of Arab invasions broke. Entire North India was under the sway of Kshatriya ruled Kingdoms, where the dominant ones were Mukharis of Kannauj, Pushyabhutis of Thaneswar and Maitrakas of Vallabhi.

The time in history when Pratihars emerged to prominence is the same when the term Rajput i.e. rAjaputra started to get popularized in community connotation. The Arab invasions catalysed another phase of new kshatriya clans replacing the old ones into prominence. A question arises. Why are early Islamic invaders noting their opponents as Rana’s, Rais and not Rajputs. Answer is that it takes time for a term to gain social currency for people to apply it to a whole community. Such a huge change doesn’t happen overnight. First the spoken languages like Prakrit and Apabhramsa adopt the change and then the classical ones like Sanskrit. But what were the catalysts of this process and why only these people of North and West India were called rAjaputras?

Northwest India was at the forefront of constant invasions from Millenias, not just in Islamic era. With Imperial centres coming and lapsing. The numerous kashatriya clans that straddle these lands at least since Panini’s time (who calls them ayudha jivin), were obviously more keen on self-reliance, sovereignty and standalone setup for their own preservation. Because they fought on all sides all the time.

The identity of medieval rAjputs as a community was however iron cast in the furnace of one such grand invasion by Arabs in the 8th century (also the core of my contention with the oxymoron called muslim Rajput). Chewing the elsewhere victorious Arabs then, was a big achievement for the currently presiding kshatriya clans in north India. They were led by nAgabhatta PratihAra, with Chauhans, Guhilots and Chalukyas in supporting role. While the bigger Kingdoms splintered around that whirlwind. The clans led by kshatriya feudal chieftains succeeded those larger empires/kingdoms of past in their own limited capacities. From the rubble of Arab storm, we see fully hereditarily operated smaller Kingdoms, now thriving & rising further. Their titles became beacons of their leadership, resistance and prestige.

Powers like Pratihars, Chauhans, Paramars, Chalukyas, Guhilots etc which rose after this epoch were fully clan based Kingdoms in military as well as administration. This happened with the completion of heredity trumping ancient republic structures in politico- military operations of people. This is how the term rAjaputra gradually gained credence for application to wider groups (kshatriyas clans that got popular Arabs onwards) later known as rAjputs.

Coming back to the quoted question. The approach itself is wrong. It is foolhardy to expect Kings before 650 A.D to use the title rAjaputra widely. Back then we had kshatriya monarchies at higher levels and tribal republics at lower levels, sprinkled with warrior clans cutting across the levels.

The very term rAjaputra was by its etymology a psychologically deep assurance to the Hindu prajA; that kshatriya descent people are still taking care of the kingdom and upholding dharma. When would you need it the most by bringing the word rAjaputra into popular usage, if not with the onset of Islamic dark age in India?

Citations:-

1 – Source citation is included in text above already. Credit: https://twitter.com/TIinExile/status/1306246761791414273

2 – Source citation is included in text above already. Credit: https://twitter.com/bhAratenduH/status/1306046147677638656

3 – Source citation is included in text above already. Credit: https://twitter.com/Dudore_0309/status/1307272002407817217

4 – Indian Antiquary vol IX, Pg 168-170; Ancient Nepal – Dilli Raman Regmi, 1st Edition, Pg 84

5 – Ancient Nepal – Journal of the Department of Archaeology, Nov 2000 Edition, Pg 22

6 – Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum vol 3, inscription nbr. 42

7 – Orissa Historical Research Journal, vol. 1, Pg 208-12

8 – Sulaiman al Tajir, translated by Eausabius Renaudot, Pg 15

9 – Indian Antiquary vol XIV, Pg 103

10 – Epigraphia India vol IV, Pg 130

11 – Annual Report of the Archaeological Survey of India 1902-03, Pg 252-53

12 – Inscriptions of Bengal vol 3, pg 73, 86, 95, 102, 111

13 – KathaSaritaSagara original text- Taranga 38, verses 90,114; Translation- Ch Tawney, vol 1, Pg 198-99; Credit: The term Rajput (Rajaputra) – Miss Padma Misra, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress Vol. 5 (1941), Pg 224-226

14 – KathaSaritaSagara original text- Taranga 24, verses 17,18; Translation- Ch Tawney, vol 1, Pg 347

15 – KathaSaritaSagara original text- Taranga 38, verse 74; Translation- Ch Tawney, vol 1, Pg 350

16 – KathaSaritaSagara original text- Taranga 74, verse 59; Translation- Ch Tawney, vol 2, Pg 217

17 – KathaSaritaSagara original text- Taranga 111, verse 24,25; Translation- Ch Tawney, vol 2, Pg 480

18 – Epigraphia Indica vol XXXI Pg 244, lines 36-37 in the plates

19 – Inscriptions from Udayagiri: locating domains of devotion, patronage and power in the eleventh century – Michael Willis

20 – Epigraphia Indica vol 30, Pg 10-12

21 – Indian Antiquary vol XIX, Pg 216

22 – Pg 85

23 – SJG Edition, Pg 11

24 – Epigraphia Indica vol XI, Pg 53-4, verse 2

25 – Source: Rajatarangini taranga VII, verse 360; Credit: The term Rajput (Rajaputra) – Miss Padma Misra, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress Vol. 5 (1941), Pg 224-226

26 – taranga VII, verses 47-48

27 – taranga VII, verses 457-8

28 – Khanda 1 (BrahmaKhanda), Chapter 10, verse 110